The Great Plains, which used to be the home of nomadic buffalo hunters, saw the development of the region's classical culture after the introduction of the horse and the influence of the peoples from the forests. In this culture, personal relationships with spirits play an important role, and myths reflect the importance of the gods of the elements and belief in a supreme being. Myths related to animals and institutions, such as the worship of the sacred pipe, are especially highlighted.

The interior of the North American subcontinent is characterized by vast plains and meadows extending from the southern forests of the ancient Canadian shield granite rock, in the north of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, to the Texas Lowlands and the folded eastern cliffs of the Rocks that reach the Mississippi Valley. Amidst these vast plains, hills rise as isolated islands, such as the Black Hills, the Badlands of South Dakota and the Sand Hills of Nebraska. The river valleys, hidden until the prairie drops abruptly, provide vital resources such as water, trees, flora and fauna, and protection against the strong breeze winds.

In an earlier era, huge herds of animals, mostly bison (or buffalo), walked under the immense sky and survived from the plentiful grasses of the prairie. Since there were no natural barriers or significant predators, the bison prospered in millions. Humans initially settled near rivers and depended on valley resources, which included bears, deer, rabbits and hunting birds. They hunted bison on foot, often trapping them in barracks or pits.

Nearly a millennium ago, some groups moved to the plains, and nomadic bands began to settle in villages, turning the fertile plains created by river groves into cultivation areas. These cultures flourished until they came into contact with European colonizers. Climate change sometimes forced adaptations in villages' lifestyle, as droughts damaged corn crops. Also, villages sometimes had to relocate due to a shortage of wood to build shelters and light fireplaces, or due to occasional conflicts. The ancestors of the mandanes emerged in the middle valley of the Missouri River and, in the late 12th century, established contacts with the ancestor of the arikaras and pawnees, who migrated from the present-day regions of Nebraska and Kansas to escape the drought, leading to a fusion of cultures in the region.

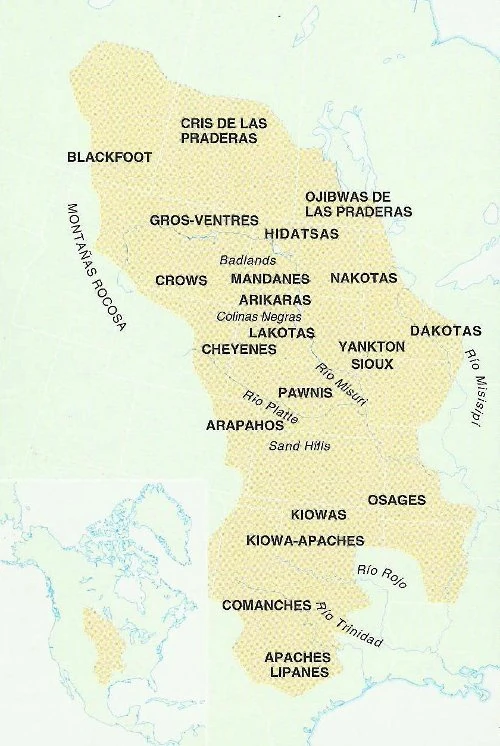

At the arrival of the Europeans, most of the indigenous communities lived in large surrounded villages along the banks of the main rivers. The pawnees lived in Nebraska, the arikaras occupied much of what is today South Dakota, and the mandanes settled in North Dakota. These groups, known as "hortellans", were skilled farmers whose lifestyle followed a similar pattern: they planted in spring, hunted bison and harvested pre-winter during summer and early autumn.

Life in the plains underwent a significant change in the 16th century, when the Spaniards reintroduced the horse, a species that had extinct in North America thousands of years earlier. The first to use horses were the pawnees, and by the end of the 17th century, other tribes in the region followed their example. The farmers found that the use of the horse facilitated their seasonal bison hunting. Some tribes from forested regions, such as the Cheyenes, moved to the plains and became farmers, but with the introduction of the horse, they also became bison hunters. This increase in mobility and migration to the plains led to new rivalries for land and resources.

Tipi played a crucial role in adapting to a less sedentary lifestyle. This conical dwelling, originally conceived by the northern tribes of the forests, was perfectly adapted to the way of life in the plains. It was built with bison poles and skins, and could be quickly disassembled and transported into wooden structures pulled by horses.

In the 19th century, the plains became a mosaic of cultures. A southern Arapaho chief mentioned that he had been in contact with various tribes, including the Comanches, Kiowas, Apaches, Caddos, Pawnees, Crows, Gros-ventres, snakes, Osages, Arikaras and Nez percé, and that he communicated with them through the sign language, which in the past functioned as a kind of frank language in the region.

The incorporation of the horse into the Great Plains brought with it numerous benefits for the native tribes, although the weapons had a less positive impact. With access to these firearms, the northern Algonquin tribes and the Iroquois League expanded to the west in search of the fur trade. As a result of this pressure, in the early years of the 18th century, the Ojibwas displaced the Minnesota Sioux, forcing them to move towards the plains. The Sioux, in turn, confronted the Mandanes, the Arikaras and the Hidatsas along the Missouri River.

The horse revolutionized bison hunting, and by the mid-19th century, indigenous hunters had significantly increased the number of bisons hunted. However, when the white settlers joined the hunting, the bison population declined drastically, depriving the tribes of the Great Plains of one of their most essential natural resources.

The arrival of white settlements, war, diseases and the extinction of the bison marked the end of the traditional way of life of the plain tribes. Those peoples who had once wandered freely through vast lands were confined in reserves. In the Great Plains, resistance to the White invasion was stubborn, culminating in the tragic Wounded Knee massacre, in which about 200 lackeys lost their lives.

The hunting method known as "The Bison Jump" took advantage of the poor vision of these animals, since as herbivores of the plains, they did not need a sharp vision. This visual limitation proved to be beneficial to the indigenous peoples, especially before there were horses. The hunters guided the bisons towards a cliff or precipice, or directed them towards a natural barracks or artificial channel created with rocks and dirt.

When the bison finally perceived the obstacle, it was too late, and often dozens or even hundreds of them perished in a single stroke.

A place in Alberta called "Head-Smashed-In" was used for more than five millennia for this hunting practice, and houses the remains of hundreds of thousands of bison. The presence of complete skeletons and bones without meat reveals that sometimes more bisons were killed than needed to obtain food, skin and other products.

However, before the decline of its population in the 19th century, the number of bisons was so numerous that it could withstand excessive hunting.

Native American Cultures: Myths and magic

Native American Cultures: Myths and magic

You can purchase this book on Amazon.

This book challenges deep-seated stereotypes and offers an enriching perspective that contributes to a more comprehensive and respectful appreciation of the indigenous peoples of North America. Through an understanding of their myths and beliefs, we are taking an important step toward cultural reconciliation and the recognition of the diversity that has enriched the history of this continent.

These mythical stories, many of them linked to the literary genre of fantasy, reveal a world where the divine and the human intertwine in narratives that explain the cosmic order, creation, and the fundamental structure of the universe. Discover how these sacred tales bear witness to the deep connection of the natives with nature and spirituality.

Native Americans: Population and Territories

Native Americans: Cultures, customs, worldview

Traditions, myths, stories and legends